CLYDE LOVELLETTE

LOVELLETTE, CLYDE EDWARD

Hometown: Terre Haute, IN (Garfield HS)

Born: 9/27/1929

Link to his Basketball Hall of Fame site

| CATEGORY | TOTAL | 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | '52 Olympics | |

| YEAR | So. | Jr. | Sr. | |||

| POSITION | C | C | C | |||

| HEIGHT | 6'9 | 6'9 | 6'9 | |||

| WEIGHT | 230 | |||||

| JERSEY | ||||||

| Games Played/Started | 80/ | 25/ | 24/ | 28/ | 3/ | |

| Points | 1979 | 545 | 548 | 886 | 91 | |

| Per Game | 24.7 | 21.8 | 22.8 | 28.6 | 30.3 | |

| Rebounds | 813+ | 192 | 211 | 410 | ||

| Per Game | 7.7 | 8.8 | 13.2 | |||

| FG: Attempts | 1713+ | 499 | 554 | 660 | ||

| Made | 811 | 214 | 245 | 315 | 37 | |

| Percent | 42.9 | 44.2 | 47.7 | |||

| FT: Attempts | 520+ | 181 | 89 | 250 | ||

| Made | 340+ | 117 | 58 | 165 | ||

| Percent | 64.6 | 65.7 | 72.8 | |||

| Production Points/Game | ||||||

| Production Points/Minute |

1950: Lettered, Starter, Conference Scoring Champ, All-Big 7, All-American.

1951: Lettered, Starter, Conference Scoring Champ, All-Big 7, All-American.

1952: Lettered, Starter, Conference Scoring Champ, All-Big 7, All-American, Helms Foundation Player of the Year. Olympic team member and Gold Medal winner.

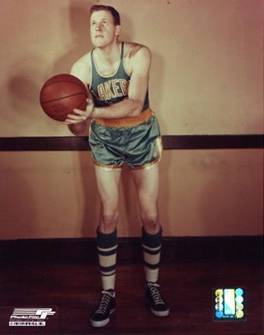

Lovellette Pictures and Posters

Clyde Lovellette Inducted Today.

______________________________

CLYDE LOVELLETE (Player 1950-52)

“In short, Clyde Edward Lovellette is basketball royalty of the highest order.” - Michael McClellan, Celtic Nation

The youngest of eight children, Clyde was born in Petersburg, Indiana, to John and Myrtle Lovellette on September 29, 1929, but he was raised in the manufacturing town of Terre Haute. His father was a New York Central Railroad engineer.

He grew into a gangly teenager, standing 6’4 as a high school freshman, and was painfully awkward and shy because of his height. “I was so awkward in high school; Mom got me a skipping rope and told me to go to it’, Clyde reminisced. By his junior year his coordination was catching up with his enormous frame. “I’d go to bed with the right length of pants.” he said laughing. “I’d wake up and the suckers would be too short.” No longer the self-conscious introvert, Lovellette blossomed on the court, earning All-State honors as a junior and senior.

Basketball was something he always loved. His growth spurt put him at 6’9, 240 pounds by his senior year, and he attracted the attention of many major colleges. He led his high school team to the 1947 state championship game. “You’d go to bed with a basketball. You’d wake up with a basketball. Girls were a foreign object.”

It was assumed he would stay close to home, playing collegiate ball in hoop-crazed Indiana, and he originally committed to Branch McCracken, coach at Indiana University, only to find the environment too large and intimidating for his taste.

“Phog was going to make a speech in St. Louis and then came to Terre Haute to meet with me instead of going back to Lawrence. I really didn’t want to meet with him, because I had verbally committed to Indiana. But I decided to meet him and that’s when he made the one statement that no other coach had ever made – he said that if I came to KU the team would be good enough to with a national championship. He also predicted that we would go to the Olympics together. "It was a beautiful idea," Lovellette decided. “that had a huge impact on me. I changed my mind because of that talk.”

Lovellette suffered from a slight case of asthma. Among Phog Allen’s attributes was his sense of humor. When asked why Lovellette wound up at Kansas, Phog told the Kansas City Star “One big reason Clyde enrolled here was because the altitude helps his asthma. Up here on the hill a tall man can stand up straight and breathe the rarified atmosphere.”

At Kansas

Thanks to the repeated overtures of Phog Allen, he chose Kansas University

instead. The chemistry between coach and player was immediate. Allen was the

mentor in whom Lovellette had been seeking. For Lovellette, Kansas turned out

to be the absolute best place in the basketball universe.

Because freshmen weren’t eligible, he spent his freshman year growing both as a person and as an athlete, further honing his skills under the tutelage of Allen. “We worked very hard during our freshman year, and then we stayed there during the summer and worked on various skills. So once we took to the court during our sophomore year, we felt that we were ready to play college basketball.” As a sophomore, Lovellette proved to be everything that Allen had predicted, finishing fourth in nation in scoring with a 21.8 per game average, was named All-Big Seven, and garnered the first of three All-American honors.

His junior year was equally successful, as he improved his scoring average to 22.8 points per game, fifth in the nation, and another All-American selection. Opposing defenses keyed on him, but he used the tactics to his advantage, developing the deadly outside hook shot that would later become such an effective weapon in the NBA.

His nice big smile, his salute, and motorcycle were a popular sight on the Jayhawk campus. While at KU, he hosted a radio show called “Hill Billy Clyde and his Hound Dog Lester.”

As predicted by coach Allen, everything did come together for Lovellette and the Jayhawks during the magical 1952 season. Clyde led the nation in scoring with 28.4 points per game. “It seemed like from the first time we stepped on the court that year against Creighton, good things were going to happen,” Lovellette told the Kansas City Star in 1988. “It just all came together. It was a great experience.”

As the team was flying to Seattle for the Final Four, its plane encountered some rough turbulence. Allen hated to fly, so Lovellette calmly took some artificial flowers that were aboard and placed them in the sleeping coach’s hands. When coach woke up, I said “Relax, Doc. If we crash, you’ve got a good suit on and they can take you right to the funeral home. That loosened him up”

No one in college basketball history dominated the sport as completely as Lovellette did during the Jayhawks drive to the 1952 title. Actually, in retrospect, the toughest time Kansas had came the night before the tournament, when Clyde went out for the evening and was missing all night. A fraternity brother of Clyde’s had become an ensign in the coast guard and was stationed in Puget Sound. He invited Lovellette for a cruise in Lake Washington and when they tried to return to Seattle a dense fog had set in, delaying his return until the following morning.

Time Magazine reported that Clyde ‘Galloped up & down basketball courts in the N.C.A.A. tournament with all the intensity, if not the ferocity, of a rampaging bear. In four games against some of the U.S.’s best teams (Texas Christian, St. Louis, Santa Clara and St. John’s) using an apparently unstoppable hook shot, Lovellette demolished every major N.C.A.A. scoring record by swishing 141 points through enemy baskets.” His 44 points in the second round against St. Louis set an NCAA tourney record, and his 33 points against St. John’s in the title game paved the way for an easy 80-63 championship victory.

He was named to Helms Foundation College Player of the Year, and left Kansas as the school’s all-time scoring and rebounding leader with 1,888 points and 813 rebounds in 77 games (subsequently surpassed by Danny Manning).

“I don’t know if you can call it providence, but we were determined to fulfill the prophesy that Phog had given us. We came together, and the team as a whole was unstoppable.”

Nicknames

Probably no athlete in history has ever been the inspiration for more

nicknames, including the Prolific Pachyderm, Cloudburst Clyde, Cumulus Clyde,

Kansas Skyscraper, Great White Whale, Ponderous Pachyderm of the Planks,

Colossal Clyde, Terre Haute Terror, and the Slendid Spike. Call him what you

will, he’s in the books as one of the all-time greats.

Olympics

Lovellette and six KU teammates were selected to represent the US on the

Olympic team, with Allen being named an assistant coach. “What a great honor to

represent your country,” Lovellette said. “Going to the Olympics was the

biggest thrill of my entire basketball career. No longer was I representing a

single state. I was representing millions of Americans with my behavior, my

ability, and my performance on the basketball court. That meant a lot to me.

Winning the gold medal was icing on the cake.”

The Americans opened with wins over Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Uruguay, before meeting the Russians in an aggressive and physical battle, which resulted in an 86-58 win behind 14 points each from Clyde and KU teammate Bob Kenney. After three more wins, they were again matched up against the Russians, in the gold medal game. The USSR, learning from their earlier loss, stuck to a strategy of tight defense and a full court stall. At halftime, the US managed only a 17-15 lead. The Reds gained the lead early in the second half, but the Americans started hitting their outside shots, and eventually won 38-25, with Lovellette leading the American’s offense with nine points.

Pros

After a season playing AAU basketball for Phillips Petroleum in 1953,

Lovellette signed with the Minneapolis Lakers. Playing solidly as a rookie,

behind the great George Mikan, Lovellette was an important factor in the

playoffs, averaging 10.5 points and 9.7 rebounds in 13 playoff games. The

Lakers won the NBA title, and Clyde became the first player ever to win a

championship at all three levels. “I didn’t know too many players in the pros. I

had to read about George Mikan to find out what everyone was talking about. And

then meeting him at that first practice was an awesome sight, because George was

a full inch taller than me and outweighed me by at least twenty-five pounds. He

was all man.”

After four years with the Lakers,

Lovellette was dealt to the Cincinnati Royals, where he toiled one year, scoring

23.4 points per game, fourth in the league. At season’s end, he asked to be

traded and landed with the St. Louis Hawks, teamed with hall-of-famers Bob

Pettit and Cliff Hagan. “The three of us just jelled together. We were the top

scoring frontline in the NBA for the four years I was there.” While a Hawk, he

registered two All-Star appearances. In 1960, the Hawks bowed to the Celtics in

seven games for the NBA title, and lost again to the Celtics in five games the

following year.

After four years with the Lakers,

Lovellette was dealt to the Cincinnati Royals, where he toiled one year, scoring

23.4 points per game, fourth in the league. At season’s end, he asked to be

traded and landed with the St. Louis Hawks, teamed with hall-of-famers Bob

Pettit and Cliff Hagan. “The three of us just jelled together. We were the top

scoring frontline in the NBA for the four years I was there.” While a Hawk, he

registered two All-Star appearances. In 1960, the Hawks bowed to the Celtics in

seven games for the NBA title, and lost again to the Celtics in five games the

following year.

Red Auerbach of the Celtics picked up Lovellette for the 1962-63 season to provide backup relief for Bill Russell. Lovellette played solid basketball over the next two seasons, helping the Celtics to win two more NBA championships. “It was really special to be a part of the Boston Celtics.”

He retired in 1964, after 11 seasons in the NBA, saying the train travel and rigorous schedule had worn him down. “I got tired. We played on the average of five games a week and in between you’d travel. I learned a lot and I experienced a lot.” He finished his career with 11,947 points (17.0 points per game), and 6,663 rebounds (9.3 rpg).

Retirement

Back home in Terre Haute, Lovellette worked as a radio and television

announcer. Then he realized a boyhood dream of being elected sheriff of Vigo

County, where he won the election by 8,000 votes. He took office in 1967 and

made good on a campaign promise to close down a red light district and some

gambling dens, before being defeated after one term.

He returned to radio, raised cattle and then headed east to Massachusetts where he taught history and coached basketball at St. Anthony’s Catholic School for a year before the school closed. After a stint as head of an Indiana country club and a failed bid to be elected mayor of Terre Haute, he was hired as a teach by White’s Residential and Family Services, a Quaker-run childcare facility helping troubled youth. Lovellette said he found his calling helping children. He stayed at the school until he retired in 1995.

During several northern Michigan camping trips, the Lovellettes bought a house in Munising and a cabin on Sixteenmile Lake, where Clyde loved to fish. He served as Munising city commissioner.

In May, 1988, Clyde received basketball’s highest honor, enshrinement in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. He is also a member of the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame and Kansas Sports Hall of Fame.

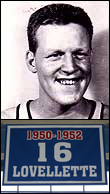

Clyde’s

#16 jersey was retired in a ceremony honoring the 1952 NCAA championship team on

February 15, 1992.

Clyde’s

#16 jersey was retired in a ceremony honoring the 1952 NCAA championship team on

February 15, 1992.

Sources (Books and Articles):

Sources (Internet Biographies):